lessons from donation based yoga pt.2: reclaiming stress and pain in the body

on being triggered, mind-body connections, a place for violence, and post-colonial ramifications (tw: corporal punishment, child abuse)

I can’t remember what my reference point for feeling triggered was before that Sunday afternoon yoga class. I thought I understood definitionally what people meant when using the term and empathized with stories of unexpectedly being thrust back into the experience of a traumatic past, but it wasn’t until I stood with my arms above my head as Colleen cued for all of us to continue pushing upwards as though lifting something heavy that I knew for sure. My hands clammed up, my thoughts started to race, and Colleen’s voice grew fainter and fainter.

At six years old, my elementary school at the time is just around the corner from our apartment building, so it takes less than five minutes for my mom to drag me from the front row of the school auditorium to our own front door. The entire way home, as she jerks my arm violently forward, I try to explain what really happened as she refuses to listen. She’s ranting about the embarrassment, about seeing each of my classmates receive an award at the year-end assembly except me. She mutters to herself about my talking out of turn and interrupting the teacher, wondering how it had gotten so bad that I had finally been publicly singled out.

Behind her, I continue my pleas like pleading to a solid wall. I tell her that my award was scheduled to come at the end of the ceremony when the best student from each grade is rewarded, but she doesn’t believe me. She finally stops, turning to glare at me and make sure I know none of my stories will be entertained tonight.

We make it into the building and up five flights of stairs—the elevator works once in a blue moon—before she finally slaps me. Truthfully, I’d expected the first slap to come as soon as the auditorium doors shut, but she’d had the self control to wait until we were in the privacy of our own building to punish me.

Once we entered the apartment, she instructed me to kneel down and raise my hands. I was used to this by now, the way she’d make me hold the position as she sat watching tv on the couch, reaching for the belt she kept beside her each time my elbows buckled because my arms were too tired or I doubled over in pain due to abs yet underdeveloped for the physical task I was handed.

Typically, the punishment lasted until one of my ‘I’m sorry’s’ finally sounded genuine enough. She’d pause her show, ask me if I would do it again, and then open her arms to embrace me before sending me to my room.

That night, she went to bed.

I’m six years old and I’m on my knees with arms raised above me and I’ve been like this for four hours because my mom didn’t believe I was really getting an award that’s sitting in a dusty drawer now and I’m saying sorry over and over to an empty living room because everyone is in bed.

In the pitch black, at 2 am, my dad gets up from bed and comes to get me.

Years later, I would overhear her on the phone complaining about how frustrating it is to have a child who doesn’t respond to simple whoopings. Who stares you blankly in the face after you backhand her and doesn’t cry. Who you have to break.

My mother never really stood a chance. Having attended Catholic schools in the period immediately after Nigeria’s colonial era, she’d spent her childhood getting beaten by nuns at school and any one of her father’s junior wives at home. My father’s experience was even more heartbreaking: at his school, most beatings occurred because a student spoke Yoruba instead of the enforced English. Speaking verna could get you slapped across the face or caned across the back. Unfortunately, in the small villages of 1970’s Southern Nigeria where it was commonplace to know only your native Yoruba, many pupils would leave school for good once fed up with the violence enacted on them day in and day out.

Dad sometimes reminisces on his old classmate Fola. The teachers never knew how funny he was—he was funny in a forbidden tongue.

I’d come to learn as I got older that my parents’ experience wasn’t unique. Sitting in the living room after Sunday dinner with a few church members, I was confronted with the ease with which they all shared stories of corporal punishment in school as just part of growing up. Many of the punishments took the form of outright torture: they described being forced to kneel on sand for the duration of their maths exams and teachers who reveled in devising new methods of control over their student’s bodies making them stand on one leg before the class as they attempted to read aloud in the difficult, grating official language of education.

In our living room, they took turns standing and demonstrating more and more difficult positions they’d been or seen others forced into. Sometimes, they weren’t even the victim and instead reminisced on being selected by the teacher to hold a pupils arms or legs while they were caned for dirty fingernails or a missing assignment. They laughed and laughed, but flinched on occasion as their bodies remembered the fear that their instructor might miss the student he intended to cane and hit one of the holders instead. It dawns on me that school and violence go hand in hand for them. That so many different things register as a call to enact harm.

I shrank into a corner, wondering if brutal punishment would always be a cultural rite of passage, and felt hope leave my body.

It had been over a decade since I’d been forced to kneel down and raise my hands (sometimes for hours on end while my family slept, sometimes carrying textbooks and heavy blocks, almost always with the threat of the belt if I couldn’t do it). I was in a yoga class in Brooklyn, not a basement apartment in Queens that somehow held three families or a lonely home in South Carolina. Yet as the class continued through the motions around me, I was stuck.

I was actively making the realization that I associate most physical pain and stress on the body with being punished as a child. As a result, I have often struggled with willing engagement with exercise because of this association. I had not been afforded the opportunity to experience my body as a site of progress—something that can do great things, hold stressful positions longer and longer to increase my flexibility and physical strength—as early as I was taught the body as a danger, something other people may harm if I stray too far from established norms of behavior.

Because this was a trauma-informed yoga class, I took a child’s pose to calm myself and gather my thoughts. Opening the journal Colleen recommended we bring for moments such as these, I filled one page and then another and then another with everything I was feeling.

I was being seized with memory at inopportune times because I had not yet sat down with myself and cried for the award I never got or for the hours I spent kneeling on hard floor to a chorus of snores. I hadn’t let myself feel the pain of a difficult childhood, and that pain had decided my time was up.

On the other side of that difficult yoga class, though, was a sort of joy that came from recognizing that I was rewriting what stress and pain mean in my body. Where previously my only reference point for stress in my arms was trying to hold up those wobbly twigs, I could give myself a new one: making myself stronger in a yoga class alongside so many other queer bodies trying to do the same.

I had something of a gym bro era kick off after this session, adding weightlifting to my exercise routine. For the first time, I’ve stuck to it. When my muscles feel tense as I attempt a heavier lift, I feel I’m actively rewiring my brain to change its primary association with feelings of pain from punishment to achievement.

Because of the social prevalence of abuse—be it corporal punishment at institutional levels the way it was for my parents’ generation, whoopings in the home, or violent fistfights at school—many people are struggling with mind-body disconnection. many are unaware of why they’re plagued with racing thoughts and bouts of anxiety at random times, not knowing something has reminded the body of a hard time, of a memory the body wants to be free of.

I go to yoga and I lift weights. I feel my muscles strain under the pressure and know I’m making myself stronger. I’m sore the next day in a way I like.

Those that came to school with elbows scraped up from falls off skateboards confounded me because I associated falling with being pushed and crying with being harmed. I used to think my classmates who came to school with scars up and down their arms from the family pet were completely out of their minds. I understand a bit more now how a scar is less unpleasant when it comes from doing something one loves, even embracing a deranged cat.

Sometimes, my butch lover gets a little carried away. A few weeks ago, after we’d gotten completely lost in one another and they’d fucked me into the floor, we found carpet burns just above my tramp stamp and deep into both of her knees. I’ll confess that those carpet burns made me giddy and giggly for the remaining four to five days that I could feel them. When my lower back would stretch, the slight sting reminded me of being everything to her in that moment, of her obsession with me. It’s nice for a scar to finally just mean love, for pain to be a reminder of passion.

I get tattoos because that pain is making this body one I want to spend even more time in. One I want to immortalize through photos.

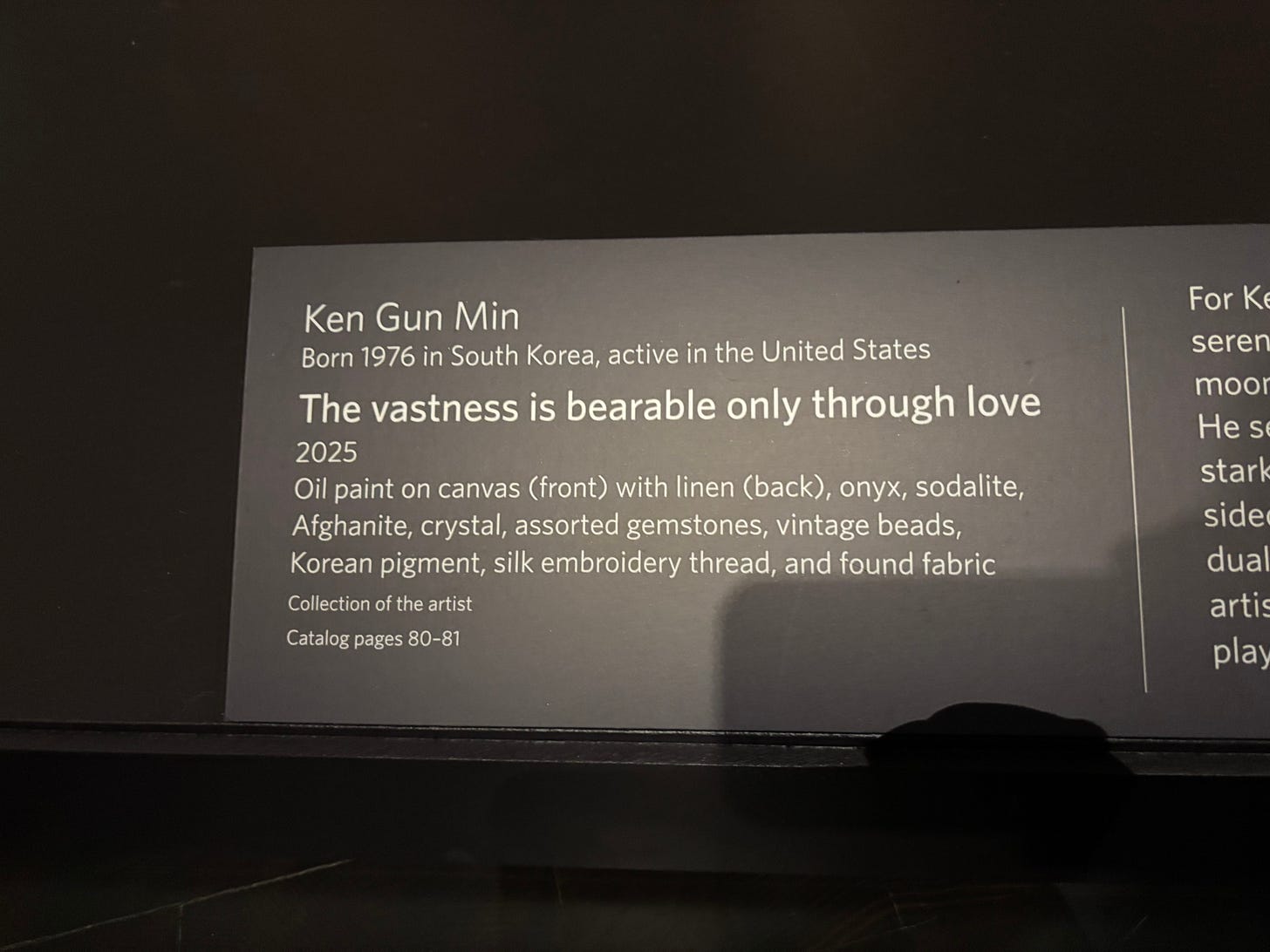

The violence people enact toward each other upsets me, because I can now see so many better outlets for it. During my 25th birthday trip, I went to the Denver Art Museum the way I always do when I visit a new city. One exhibit featured Korean Moon Jars—giant, globular, white vessels that symbolize a number of things such as the aesthetic value of imperfection (the jars are made by joining two halves that are never truly identical) and the beauty found in simplicity. The hall was filled with dozens of jars, paintings of jars, textile representations of jars, but the piece that called out to me the most was a video of the process of a Korean Moon Jar being created.

As artist LEE Dong Sik went through the process of creating his jar, I thought to myself, “this is violent, and it is beautiful.”

LEE spreads clay on the floor, and then marches and stamps on it to create the consistency he wants. After he grounds the work into the earth with his feet, he takes a knife to it to create his desired shape and to score both halves, making it easier for them to stay together. He presses his thumb along the seam, then using a metal paddle, smacks the jar over and over again as he spins it. The jar is thrust into fire above 1000 degrees Fahrenheit. Some jars collapse under the pressure or shatter in the heat.

The resulting works are beautiful, the end product of a stunningly laborious process, and LEE unwittingly provides evidence of the place for violence: within creation and art rather than against the bodies of children and pupils.

I contrast the impact of experiencing violence in this context with the memory of violence that overtook me in that yoga class and got me thinking about the topic all those months ago. I’m sitting in the Denver Art Museum, freshly fucked from the night before, taking in art, thinking about violence, and I can breathe.1

As of 2014, West African researchers in Nigeria and Ghana catalogued nearly 15 types of corporal punishment in schools still enacted as a method of prevention against student indiscipline. These methods include forced kneeling or standing for long periods of time, slapping or beating the pupil, flogging the pupil with a stick or cane, and even pulling ears and/or hair. Researchers also find these methods to be largely ineffective. (From: Corporal Punishment: Perceptions and Adoption in Nigerian Secondary Schools)